The smell of the sage and chaparral always takes me back. It was the Grand Canyon of my youth. It was deep, dark, and scary as hell. Like a game, it pulled me in: small and simple at the start but complex and mysterious at the end. One of its secrets was a crevice, scoured by the 1966 floods, that started a few feet deep surrounded by lizards and birds and ended hundreds of yards later in a 20-foot deep narrow crevasse with snakes. It took me and my 8-10-year old friends years to conquer our fear of that place, to fully discover the wilderness in our backyard. By then I was an experienced explorer, and it set me on a path in life that serves me to this day. They were the canyons of my youth but they are long gone.

The suburbanization of rural lands is a familiar story for those growing up in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. It was a consequence of the post-WWII baby boom and the development of the suburbs across America. Prior to that time, most people lived in cities with farmland occupying flat, open space. But those involved in the war married and sought–and deserved–the American dream: owning a new home. The ensuing population boom and housing crisis was met by our country’s newly burgeoning industrial might and ingenuity and the suburbs arose as a solution. Through that process, mass-produced homes — the tract home — were developed as they could be built efficiently with minimal waste. It was a good solution for its time, and continues today, but it had a cost that would only be realized later: significant impacts to the environment and the loss of open spaces.

As Adam Rome discusses in his seminal book The Bulldozer in the Countryside, poor planning led to new and undiscovered impacts on water, soils, and wildlife due to the construction of septic systems, destruction of wetlands, building on floodplains and earthquake faults, and the loss of virgin land. Adding to that was the search for the “perfect turf” surrounding our homes. The synergy created by these complex issues helped build the 1960s environmental movement, culminating in Earth Day, and many of our existing environmental laws. Truth is, many cities and counties still struggle with these issues today, a casualty of poor environmental planning in the past.

But to me, it was all about my playground, the canyons. I wasn’t alone. As Rome writes: “In new subdivisions, children were often able to play in undeveloped land nearby–then one day the bulldozers would come to turn those playgrounds into lots for new houses, and people of all ages reacted with shock and outrage.” In 1962, for example, a seven-year-old boy from California made national news when he sought the help of President Kennedy after discovering that development was destroying his favorite place to hunt for lizards (original text).

Dear Mr. President,

we Have no Place to go when we want to go out in the canyon Because they are going to Build houses So can you setaside some land where we can Play? thank you four listening love scott.”

That letter could have been written by my 10-year old self from my experiences in Pacific Beach.

San Diego was at the forefront of urban development. Between the 1950s and 70s, the population doubled and then doubled again in the following three decades. Where I grew up, in Pacific Beach, most of the city was located on flat land near the ocean, established in the late 1880s from railroad transportation. For almost a century after that, the rugged hills with sweeping views of Mission Bay sat empty. Then in the early 1960s, the Pacifica Drive area, despite steep inclines and a rugged landscape, was rapidly developed. My former home on Amity Street, where I Iived from 1966-1968, was built in 1964, the first phase of several. Over a hundred homes were constructed in that area in 1961-64. Our canyon, as I was to discover later, was smack-dab in the middle of the “straightening” of Soledad Mountain Road — a project to reduce the transit time from PB to La Jolla. Although I didn’t make the connection at the time the dozen dead-end roads leading into the canyons now seem ominous.

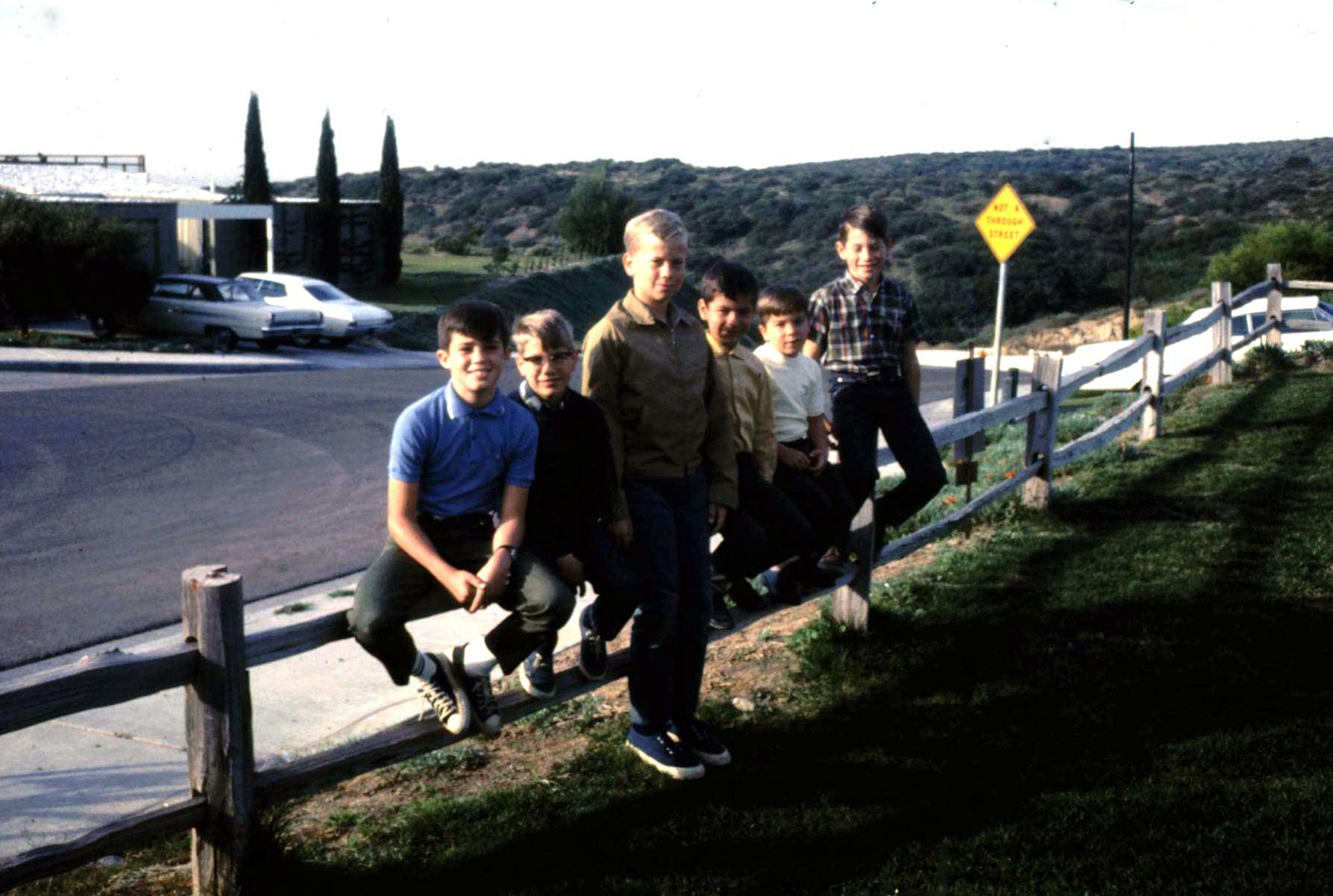

But for three years in the mid-1960s, my friends and I explored the amazing canyons at the end of our street. In those days my mom would kick me out of the house after breakfast (my father was in Vietnam at the time) and call me and my brother in at dinner time. So we had the whole day to explore, at least during the summers. I remember tree forts, rock fights, playing army, and walking around making discoveries.

As I wandered the rugged sage-chaparral landscape I saw hawks soaring in the canyon thermals, quail running with their young across the trail, and lizards sunning themselves on rocks. I’ll never forget discovering fossil scallops in a road cut, which sparked a lifelong interest in paleontology. Our nemesis, the western rattlesnake, was mostly heard but unseen, a constant reminder of the dangers we faced. I remember big snakes coming up the roads of our dead-end street in the evening and scaring the hell out of my mother. But now I understand they were probably just following their ancestral paths up the hills, now covered by asphalt.

Treasures of Pacific Beach canyons (clockwise from upper left): rattlesnakes, hawks, lizards, quail, and fossil scallops.

After conquering the canyons and the crevasses we moved on to the storm drain at the southern dead end of Soledad Mountain Road and discovered the streets underneath PB. Exploring the huge, dry pipes with a flashlight and skateboard, I remember popping up in street drains and under manhole covers as our world grew with our newfound courage. By then my spirit of adventure was set.

But my father was in the Navy so we moved away in 1968 to McLean, Virginia then Idaho Falls in 1969. As an experienced explorer, at 11 I hiked the Appalachian Trail and at 12 I snowshoed into the Grand Tetons as a Boy Scout. I returned to PB in 1970 and lived on Olney street near Kate Sessions Elementary, my former school in the 1960s. I recall riding my bike up to my old house on Amity St. and being disoriented by the roads, which I knew well from my newspaper routes, and was astounded to see that my canyon was gone. Somehow, the rugged landscape had been graded and filled with homes and roads. These days, Soledad Mountain Road, which runs right through my old proving grounds, serves 10,000 vehicles a day and shortens their trip to La Jolla from PB by a few minutes. I hope the time saved is appreciated.

Thankfully, due to the efforts of others, part of that undeveloped area remains as Kate Session Park. The namesake for my elementary school, Kate Sessions (1857-1940), the founder of Balboa Park in San Diego, was a remarkable woman that appreciated open spaces and native plants. She moved to Pacific Beach in 1912 and made it her mission to preserve open space and restore native vegetation. Now, through her pioneering vision and efforts, many can still enjoy part of the area I used to explore as a child and made me the scientist I am.

Looking back I realize I was part of the suburbanization of those hills and valleys. They were a treasure to be enjoyed but not held. Now they are just a deep memory. But one where I often retreat to for solace as time marches on and nature continues to vanish. Like the canyons of my youth.

References:

- CalTrans, 2011.Tract Housing in California, 1945-1973: A Context for National Register Evaluation. 209 pp.

- Kate Sessions in PB. OriginallyPB. Accessed Jan. 21, 2019.

- Kate O Sessions Memorial Park Check List, iNaturalst.Accessed Jan. 25, 2019.

- Rome, Adam. 2001. The Bulldozer in the Countryside. Cambridge University Press.

- Webster, John. 2013. Originally Pacific Beach: Looking Back at the Heritage of a Unique Community. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. 256 pp.

13 responses to “The Vanishing Canyons of My Youth”

Great article…we did the same in Clairemont area…while my dad was flying F8s over Vietnam Suzanne Mc Daniel

Sent from my iPad

>

Wow, interesting. I remember that area being developed (my family were farmers in Chino). Unfortunately, I guess it was a common experience.

Say Hi to your dad from McDaniel Family

Thank you for the articals on the vanishing canyons story.I like you grew up with the canyons.Grew up in Mission Bay during the same period,maybe a few years before you,I’m now 65 years old.I miss how Pacific Beach used to be.It’s nice to talk to some one that remembers it.Thank you a lot Greg Sousa

________________________________

Thanks Greg, I miss the old PB too. It was a great place to grow up.

Again another great article about the past. Thanks. Cousin Mike

Thanks Mike! Appreciate the feedback.

Hea Brian, really nice writeup, I could totally identify with it growing up in San Diego. My canyon was Tecolote at the south end of Clairemont which separated my neighborhood from the hill that the University of San Diego is on. But some of it is still there and wild, the rest is a new neighborhood that covered up the south end of it, with parkland that extends to the east, then wraps around to the north to where there is the Tecolote Golf Course. We used to ride our Flexys down thru the big drain pipes from our street, down to the bottom of the canyon, our first tube rides. It was such a huge part of my life growing up, back when it was 100% wild, that I had long ago decided that if I ever had a son, I was going to name him Canyon, but that never happened.

Anyway nice site, first time here, cool to read, and long time no see, hope all is well with you. GB (the Burg)

Hey Greg, it’s great to know that we shared similar experiences. I’m hearing that from quite a few people in California. It least some wilderness remains and we have our memories of what it was like. Glad you like the site, it is fun to write and reminisce about the past. We got it good.

My parents moved to Linda vista in 1941 into “temporary” housing for consolidated voltaire (later convair). The canyon behind us we called the Mesa is now mission heights. We built forts, played cowboys and Indians, marbles. Caught horny toads (lizards) and went through the pipes under 163 to catch polywogs where hazard had buffalo. Boy were we upset when the bulldozers came in there to clear out our canyon for homes.

[…] and activism in our universities; the young who grew up with the joys of hunting, fishing, hiking, and camping while burgeoning suburbs ate away at their playgrounds in the fields and forests of […]

[…] One reason is demographics. San Diego was at the forefront of urban development in California and between the 1950s and 1970s, the population doubled and then doubled again during […]

Hi Brian…Thanks for the cool article. We shared similar experiences a short distance apart. My canyon was Red Canyon or Bird Rock Canyon. Tourmaline Canyon before the “improvements” was also my stomping ground. Flexies down all the drainpipes in the area were also part of my youth (I´m 77 now). You might like to check out my article “Memories of Bird Rock, La Jolla, California, 1945-1965.”

https://independent.academia.edu/HarryMarriner

Do you have any idea when the part of Tourmaline Canyon crossing PB was filled in?