He wanders free beside the sea,

Wher’er the coast is stony.

He flaps his wings and madly sings,

The plaintive abalone.

We sit around and pound and pound,

But not with acrimony,

Because our object is a gob

Of sizzling abalone

— The Abalone Song

The abalone song hearkens back to a time long gone. A time along the west coast when life was simple, carefree, and abalone were plentiful. A time when you could walk along the shore at low tide and harvest your dinner in minutes. But those times are gone, gone with the tide you might say. When the tide was high, in the 1950s and 60s, over 4,000,000 pounds of abalone were harvested per year (about 2 million abalone) in California; when the tide was low, in the late 1990s, commercial fisheries were closed, with two species of abalone (white and black) eventually ending up on the endangered species list. I was lucky, as I was able to see some of those days: when, in the 1960s, my brother brought home a gunny sack of green abalone from Sunset Cliffs near San Diego; when you could buy an abalone fillet for under a dollar in the hamburger stands in southern California; when abalone were so abundant in the 1970s and 80s they carpeted the landscape in the California Channel Islands; and in 1986 when I visited Natividad Island in Baja California and saw the last years of their once flourishing abalone fishery.

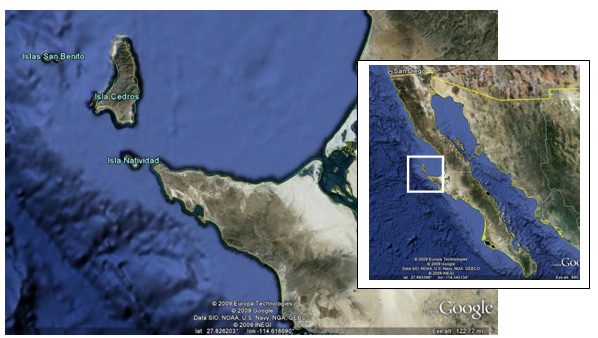

It was the summer of 1986 and we had embarked on the ultimate surfing ecology road trip. Combining my interests of surfing and marine biology we set off looking for abalone and good, uncrowded waves. I had just starting my PhD dissertation and had established study sites and tagged black abalone in northern and southern California. Baja was next. Cruising with my college buddies Paul Dunn and John Steinbeck we picked up Alberto Pombo, a colleague and scientist at CICESE in Ensenada. Together we cruised south and days later we rolled into Bahia Tortugas (Turtle Bay) and caught a fishing boat out to Isla Natividad: a place known for outstanding waves and an abalone fishery. Alberto helped us hook up with an abalone fisherman and we spent several days living with him and his family. In Mexico all commercial fisherman are members of a fishing cooperative, in this case the Buzos y Pescadores de Isla Natividad Cooperative. They were incredible gracious and the next day took us fishing for abalone.

They had been fishing this way since the 1950s. After a quick breakfast of café con leche and tortillas we left early in the morning in three small boats and headed up the east side of the island to the NE side, an area they had fished for some time (area “A” in Shepherd et al, 1998). Each boat had a Hookah diver, a captain, and a tether handler. Hookah is a method whereby air is pumped from a compressor down to the diver through a tether. The advantage is that it is simple and there are no tanks, so the air can be supplied for long periods of time. The disadvantage is that you need to be careful that the tether doesn’t get crimped or broken and the endless air supply allows divers to stay down too long and potentially suffer from the bends (decompression sickness). The boats worked hard for 6-8 hours. Contrary to common diving practices they started in shallow water (15-20 feet) and moved deeper (60-70 feet).

Every 20 minutes or so the diver would surface and pass the catch, 5-10 abalone, to the boat tender. The tender would then measure each abalone to make sure they were of legal size (5 inches in Mexico at that time); undersized abalone were returned back to the bottom. As I watched the divers progress over the reef I was amazing by their progress and due diligence Every 30-40 min or so a net would come up to the boat full of abalone; very few were undersized but those were returned to the ocean. The diver took one break during the entire day and we feasted on freshly caught abalone, pounded and fried right on the boat and wrapped in a warm corn tortilla. It was the best I ever ate!

We learned from the boat crew that this was the way they had done it for many decades. They all talked about the “golden” days of the fishery in the 1960s and 1970s when abalone were much more plentiful and fishing was easier. They pointed to the channel between Natividad and Cedros Island as an area where abalone used to be very abundant. And in the 1970s they moved into that area to harvest white abalone: a deep water species that required diving at 90+ feet depths. According to their stories they had high catches of whites for several years but many divers were injured in the process through decompression sickness.

After a days worth of work we were back at the dock by mid-afternoon: our boat had caught about six dozen abalone. Mostly greens but some pinks (their preferred species). We watched as they cleaned the entire catch and weighted each boat’s contribution. In total contributions from about 10 boats I estimated a total of about 800 abalone, about 1700 lbs.

Just prior to our visit the fishery was recovering from intense fishing and the devastating effects of the 1982-84 El Niño, which had a strong negative effect on abalone (Del Proo, 1992). The fishery subsequentially collapsed and was closed in 1984, then reopened just before we arrived (Shepherd et al., 1998). After that the fishery recovered some then declined again. Although it is still active now (in 2016) it is a small remnant of its former self but still an active fishery. It persists largely because the cooperative fishery model which includes TURF (Territorial Fishing Rights) works well with the islands resources (McCay et al., 2014) and the community has a diverse resource base including lobster, turban snails (Megastraea spp.), sea cucumber, sea urchin, and seaweed. In addition, the establishment of MPAs (marine protected areas) in the island are promoting abalone recovery in some traditional areas (Afflerbach, 2013).

Thirty years later, looking back on those three days on Natividad, I feel very fortunate to have been there. At that time we had no idea that we were witnessing the end of an era. And of course that goes for anything these days: on this rapidly changing planet how do we ever know where things are going? What does the future holds for us and our precious ocean life? At least for abalone we know they have bottomed out, with at least 200 million abalone being removed from California over the last 100+ years, and hopefully are on the road to recovery. Like the tide rising and falling they will come back again. Because the fisherman and their families on Natividad have shown they are resilient in the face of change. Ultimately the future is up to us, for the ocean takes care of itself. All we need to do is leave it alone.

References:

- Afflerbach, J. 2013. TURF-Reserves at Isla Natividad Baja California, Mexico. 2 pp.

- Buzos y Pescadores de Baja California (Divers and Fishermen) Cooperative

- Guzman Del Proo, S. A. 1992. A review of the biology of abalone and its fishery in Mexico. In: Abalone of the World: Biology, Fisheries and Culture, Shepherd, A. S., M. J. Tegner and S. A. Guzman del Proo (eds). Wiley-Blackwell

- McCay, B. J., F. Micheli, G. Ponce-Diaz, G. Murray, G. Shester, S. Ramirez-Sanchez and W. Weisman. 2014. Cooperatives, concessions, and co-management on the Pacific coast of Mexico. Marine Policy 44: 49-59.

- Shepherd, S., J. R. Turrubiates-Morals, K. Hall. 1998. Decline of the abalone fishery at La Natividad, Mexico: overfishing or climate change. Shellfish Res. 17(3): 839-846.

5 responses to “Gone with the Tide: the Abalone Divers of Isla Natividad”

The decline of the fisheries in the region led to an increase in poaching that resulted in violence and deaths. The following article, explores that unfortunate phenomenon. And yes, without knowing it in many ways, (not only the abalone fisheries industry) we were witnessing the end of an era.

Fishers’ Reasons for Poaching Abalone (Haliotidae): A Study in the Baja California Peninsula, Mexico. North American Journal of Fisheries Management Volume 29, Issue 1, 2009

Ricardo Bórquez Reyes, Oscar Alberto Pombo & Germán Ponce Díazc DOI: 10.1577/M06-032.1

[…] From there we learned about the DUKW (the Duck). One of the challenges of getting from shore to a ship is motoring. The Duck is the ultimate amphibious vehicle. So we loaded up our science gear, wetsuits and boards and climbed into the duck on the beach at Bahia Tortugas. Destination: Natividad; a remote offshore island with mythically perfect waves. From the Duck we transferred our gear to a fishing vessel for the 10+ miles ride out to Natividad known for both surfing and abalone. […]

[…] research on black abalone on Año Nuevo Island and Santa Cruz Island in California and in Baja California in Mexico. I wouldn’t dare do anything of these things now as they would likely kill me! […]

[…] Gone with the Tide: the Abalone Divers of Isla Natividad […]

This takes me back to my childhood on the beaches of 1950s La Jolla. We kids would play among the rocks and tide pools while our dad and his buddies would dive off the coast.

Back then, abalone-reds, greens, pinks and blacks, were plentiful and even visible in shallow water. Divers would take a deep breath, submerge with ab iron in hand, using the deft moves required to gain the element of surprise to quickly pry them from the rocks before the abalone could fasten themselves too tightly for removal. Only the experienced and fit could be successful at this enterprise.

We helped guard the catch on the beach, watched our dad pop them from the shell, clean, slice and prepare them for cooking. The reward for this combination of skill and endurance was a feast for the gods. There is nothing in the world like abalone pounded, breaded and flash fried in an iron skillet.

In the early 1960s, commercial abalone “fishing” began in earnest. Abalone were stripped from the most accessible spots. As these places were depleted, deeper waters were exploited. Poaching was a regular occurrence.

As abalone gained in popularity, amateur divers wearing tanks began taking them from shallow water, easy access for the inexperienced. More was taken than needed and the pillaging continued.

And so it went. Abalone have literally been removed from their habitat. Along with all the other environmental assaults on our shores I often wonder what impact the removal of these numbers of abalone has had on our rocky shoreline.