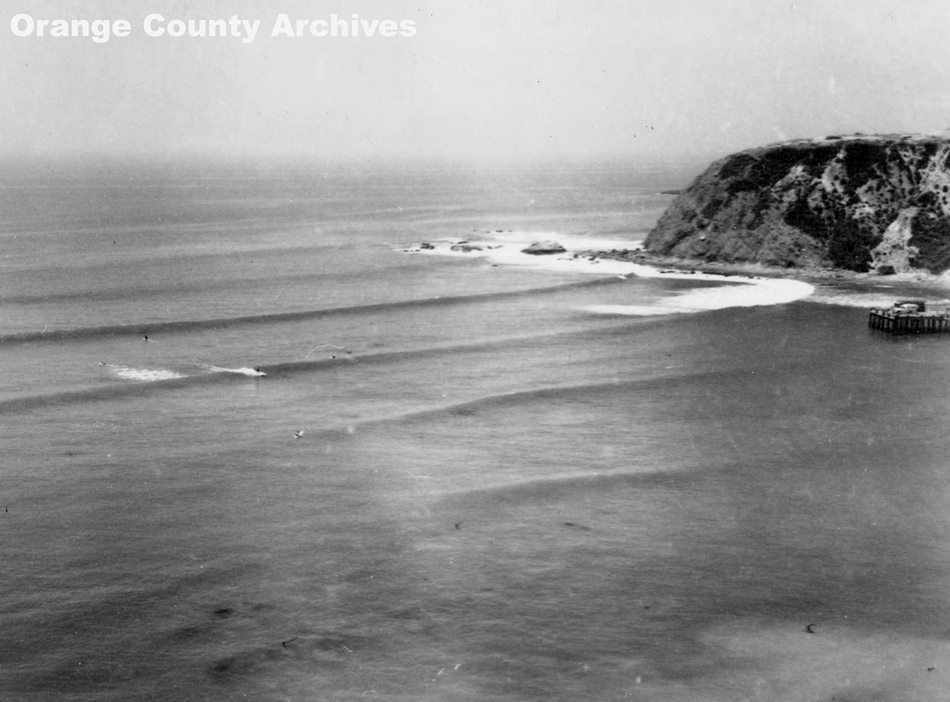

Among the powerful slogans used in the battles to protect surf spots along the coast of California, that of “Killer Dana” still resonates among the surf community. The loss of Dana Point, and it’s renown right point break, should serve a stark reminder of what could happen without the protections we currently have in place. Dana Point, in many ways the birthplace of the surfing industry, was notorious for focusing deep-water south swells on a long, rocky point break, creating one of the best big-waves spots on the coast at that time, not to mention the day-to-day fun surf. According to surf historian and Dana Point surfer Allan Seymour “The thing about Killer Dana is that it was the only place that would hold a 12 or 15-foot swell,” he said. “And these were huge, freight train-thick swells. And the prevailing wind was westerly coming over Dana Point, which made for offshore winds from Doheny to Killer Dana.”

In the 1950s and 60s, the town developed plans to build a marina in Dana Harbor and construction began on the $100 million project in 1966. A group of surfers, led by Ron Drummond, worked to stop construction, but the loss of the wave, and any damage to the ocean, was considered insignificant compared to the economic benefits of the new marina. As Jeremy Evans writes in the Battle for Paradise:

When the first of many boulders was dropped in 1966, specatators stood on the shore and clapped, marveling at the sight and excited for the future economic boost. Killer Dana’s surfers were also there that day, powerless to stop what they considered to be nothing more than aquatic rape. They were saddened and stunned as the bouders were dropped into the cove, which had been the setting for some of their greatest surfing memories and was, to some, their second home. For others, it was their only home.

Thus, was born surf activism in California. Back then, in the 1960s, there was no NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act, 1970) nor its California counterpart CEQA (1970), which required public meetings and extensive planning prior to major construction projects like Dana Cove. There was no Clean Water Act (1972), which regulated the location and discharges of developments and power plants; no Coastal Commission (1972), which providing regulatory oversight of the coastal zone; and no Surfrider Foundation (1984), who fought for the interests of surfers. Then, the only warning for some projects was the posting of a construction permit and the arrival of bulldozers.

In was also a critical time in the state’s history. Developers and urban planners had developed proposals for most of the coastline to create a series of “atomic cities”: regional developments centered around marinas, high-rise developments, nuclear power plants, and interconnected freeways. And this happened throughout much of southern California in Marina del Rey, the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, Newport Beach, Dana Point, and San Diego. As backlash against such rapid developments began, the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill galvanized many into action and Californians approved Proposition 20 in 1972 to establish the Coastal Commission.

Since the establishment of the Commission, and the passage of the California Coastal Act (1976), the state has successfully blocked offshore oil drilling and leasing, restricted coastal construction and development, and expanding public access to beaches. Planned developments at Davenport, Bodega Bay, Sea Ranch, Shelter Cover and other areas were modified or stopped. The meaning of all this for California is profound and often unappreciated. David Helvarg, in his seminal history of California, The Golden Shore, writes:

Why is it that almost half the coastline of the most populous state in the nation, a coastline that’s also arguably among the most scenic and spectacular in the world, is so thinly seeded that the largest coastal city between San Francisco and Portland, Oregon, Eureka, California, has a population of just twenty-eight thousand? Even today, with twenty-five million Californians living in coastal counties south of the Golden Gate, the five coastal counties north of the bridge: Marin, Sonoma, Mendocino, Humboldt, and Del Norte have a combined population of fewer than one million people and more than two-thirds of them live in Marin and Sonoma within commuting distance of San Francisco. How come the very serviceable harbors at Bodega and Humboldt Bay aren’t major port towns or at least swarming with summer tourists like you find on Cape Cod, along the Jersey Shore, or on North Carolina’s outer banks? Part of the answer is climatic, part economic, and the rest I’d attribute to the sprawl-preventing California Coastal Commission.

It’s important to remember that these battles are still ongoing. As Peter Douglas, the executive director of the Commission for 26 years, once famously said: “The coast is never saved. It’s always being saved.” As evidence, recall the 2016 agreement that ended one of the most hard-fought, long-lasting environmental battles in California history over the building of a freeway through San Onofre State Park, which would have destroyed Trestles. It took surfers, the Surfrider Foundation, and a broad coalition of environmental groups and native American Tribes years to push for a successful agreement. Even after these prolonged struggles, the decision often hangs by a thread. In the case of San Onofre, a hard-fought victory and “permanent” agreement is being threatened once again. So the battles continue and there is always be work to be done.

So, you might ask, why the history lesson and the uncovering of old wounds in the surf community? It’s for motivation and the simple reason that current politics are rapidly changing, with many important environmental policies and institutions being eliminated. swept aside, defunded, or marginalized. Once again, the very real possibility of oil and gas drilling off the California coast has returned and who knows what’s coming next? If we forget the tragic losses of the past, the reasons why we fought, or don’t support the institutions that helped bring those changes about, we run the very real risk of repeating old mistakes. We simply can’t let that happen and Killer Dana should be a reminder for all of us.

So, here’s a few things you can do (with links to some of my relevant posts):

- Get informed and educate others;

- Get involved in things you care about;

- Support the people and organizations that are making a difference:

And remember Killer Dana!

References:

3 responses to “Lessons from Killer Dana”

[…] and reality are often stark (Pilkey and Dixon, 1998). With respect to surfers, although there are downsides, we generally come out on top, as jetties create some of the best human-made waves on the planet. […]

Sometimes maybe, but not in that case. The marina, and breakwater destroyed 2 spots outright and mauled a couple others beyond recognition. As for improvement? I don’t know of anyone who raves about surfing the Dana Point area since, but they did before.

Surfed it before the breakwater and it was wonderful. A terrific loss and horrible crime for untold generations of Southern California Surfers.